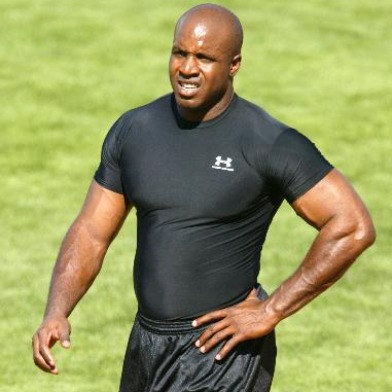

A federal jury is set to begin deliberating in San Francisco Friday on whether baseball champion Barry Bonds lied to a grand jury nearly eight years ago when he denied taking steroids.

A federal jury is set to begin deliberating in San Francisco Friday on whether baseball champion Barry Bonds lied to a grand jury nearly eight years ago when he denied taking steroids.

U.S. District Judge Susan Illston handed the case to the jury shortly before 4 p.m. today after a day of closing arguments in which prosecutors charged that Bonds lied to protect his home-run records and the defense claimed government lawyers were “demonizing” him.

The jurors met briefly and then announced they will begin deliberating at the Federal Building courthouse at 8:30 a.m. Friday. The trial began March 21.

Bonds, 46, is accused of making three false statements and obstructing justice in his Dec. 4, 2003, testimony before a grand jury that was investigating the distribution of illegal drugs to athletes by the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative, or BALCO.

The three alleged lies were his statements that he never knowingly received steroids or human growth hormone from his trainer, Greg Anderson, and never received any kind of injection from him.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeff Nedrow told the jury, “All he had to do was tell the truth.”

But “he chose not to tell the truth and that’s why he’s here,” Nedrow said.

Bonds wanted to protect “the powerful secret he had been using steroids and human growth hormone in connection with his profession as a professional athlete,” the prosecutor said.

“He had concerns it would taint his accomplishments he had achieved during his career,” Nedrow said.

While playing for the San Francisco Giants, Bonds set Major League Baseball’s single-season home-run record of 73 in 2001 and the career record of 762 during his last season in 2007.

Bonds admitted to the grand jury that he took two substances known as “the clear” and “the cream,” which were later identified as previously undetectable steroids, but told the panel he thought they were flaxseed oil and arthritis cream.

Nedrow argued, “It’s implausible on its face that a professional athlete earning $17 million per year didn’t know what he was taking.”

Defense attorneys Allen Ruby and Cristina Arguedas took a three-part strategy in their defense closing.

They argued that the prosecution lacked a crucial element of proof, that its witnesses were unreliable and that the case was a vendetta in which prosecutors were attempting to demonize Bonds.

“Theories that seek to demonize someone are really wrong,” Ruby told the jury.

Arguedas alleged, “This prosecution, in its zeal to go after Barry Bonds, will forgive anybody anything, including perjury, … if somebody will say something bad about Barry Bonds.”

Ruby said the missing element of the prosecution was proof that Bonds’ alleged false statements were relevant to the grand jury’s work.

“There has been a complete failure of proof by the government,” he charged.

Under jury instructions read by Illston at the start of the day, jurors must conclude not only that Bonds knowingly made a false statement but also that it was material, or relevant, to the grand jury’s BALCO probe before they can convict him.

Ruby contended that prosecutors never explained during the trial how the grand jury worked or how Bonds’ testimony affected what the grand jury did.

Because Anderson refused to testify–and was jailed for contempt of court–prosecutors relied mainly on circumstantial evidence from former associates of Bonds and a former girlfriend, Kimberly Bell, to try to prove that he showed signs of steroid use and allegedly was aware of them.

The prosecution’s strongest direct evidence was related to the charge that Bonds lied when he said he never received any kind of injection from Anderson.

Kathy Hoskins, a former personal shopper for Bonds, testified that she saw Anderson give him an injection of an unidentified substance in the navel in 2002 while she was packing for him for a road trip.

“You heard Kathy Hoskins testify directly that she saw him injected and that the defendant told her it was a little something for the road and couldn’t be detected,” Nedrow told the jury.

Ruby and Arguedas suggested, however, that Hoskins had a motive to protect her brother, Steve Hoskins, a former business associate of Bonds who was fired by Bonds in 2003 after Bonds accused him of theft and forgery in their memorabilia business.

Arguedas said federal investigators took the unusual step of interviewing Kathy Hoskins in 2005 in the same room as her brother while knowing that Steve Hoskins was under criminal investigation, was his sister’s employer and had promised prosecutors his sister had helpful information.

“When they did that, they compromised that piece of evidence before it got to you, and it cannot be considered proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” said Arguedas, referring to Kathy Hoskins’ testimony.

Prosecutors presented a total of 25 witnesses in the case and defense attorneys presented none.

The charges against Bonds each carry a theoretical maximum sentence of 10 years in prison if he is convicted.

But two other sports figures who were convicted of lying in the BALCO probe–cycling champion Tammy Thomas and Olympic track coach Trevor Graham–were sentenced, respectively, to six months and one year of home confinement.

Julia Cheever, Bay City News

Want more news, sent to your inbox every day? Then how about subscribing to our email newsletter? Here’s why we think you should. Come on, give it a try.