The federal judge in the perjury trial of home-run champion Barry Bonds will hear arguments in San Francisco Tuesday on a final flurry of motions in which each side is seeking to predict and forestall the other’s trial strategy.

The federal judge in the perjury trial of home-run champion Barry Bonds will hear arguments in San Francisco Tuesday on a final flurry of motions in which each side is seeking to predict and forestall the other’s trial strategy.

U.S. District Judge Susan Illston has been ruling on motions in the case ever since the former San Francisco Giants slugger was first indicted in 2007 on charges of lying in 2003 to a federal grand jury investigating steroids distribution.

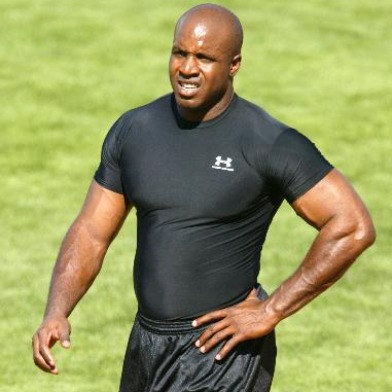

Bonds, 46, is due to go on trial March 21 on four counts of making false statements and one count of obstructing justice in his grand jury testimony. Among other charges, he is accused of lying when he said he never knowingly received steroids from his trainer, Greg Anderson, and never received an injection from Anderson.

The 15 final prosecution pretrial motions and five defense motions filed on Feb. 14 ask the judge to limit testimony that each side thinks could be unfavorable to its case.

The requests range from the cerebral to the seamy. One dispute is over whether Bonds’ ex-girlfriend, Kimberly Bell, should be allowed to testify about purported changes in his body after he allegedly began using steroids in the late 1990s.

The defense claims such testimony would be unscientific and would create a circus atmosphere at the trial.

Prosecutors, meanwhile, want Illston to bar Bonds’ lawyers from counterattacking by showing the jury nude pictures of Bell that were published with a 2007 Playboy Magazine interview about her relationship with Bonds.

The photos “add nothing except an element of prurience” to the case, prosecutors wrote.

Another prosecution motion concerns the centuries-old concept of jury nullification.

Jury nullification occurs when jurors, despite the law and the evidence, acquit a criminal defendant, either because they believe the law is unjust or because they believe it is being used in an unjust way.

The doctrine governing federal courts in California is that while jurors can never be punished for a verdict, they can’t be told about their power to nullify and a trial judge must guard against any defense arguments that could lead to nullification.

Prosecutors want Illston to prevent Bonds’ attorneys from taking a back-door route to jury nullification by barring them from asking questions of witnesses or presenting evidence that could indirectly lead to such a verdict.

“All jury nullification arguments should be prohibited, whatever incarnation they take,” prosecutors wrote.

The prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office outlined four areas in which they think there is a danger the jury could be tempted to engage in jury nullification.

One would be “asking the jury to infer that the prosecution spent too much money on this case or devoted inordinate resources to the prosecution,” the federal lawyers wrote.

References to such subjects “would be nothing more than efforts at jury nullification,” the prosecutors said.

A second forbidden area, they said, would be to suggest that the prosecution is unjust because Bonds’ achievements brought economic gain and civic pride to the Bay Area or because all elite athletes use steroids.

“Those matters are clearly irrelevant to the defendant’s guilt or innocence of the charged crimes,” prosecutors wrote.

While playing for the San Francisco Giants, Bonds set the Major League Baseball single-season record with 73 home runs in 2001. He reached the career record of 762 in his last season in 2007.

The final two prohibited areas, prosecutors said, would be suggesting that “bygones should be bygones” because the alleged lies occurred almost eight years ago, or that Bonds has already suffered enough from allegations of steroid abuse.

Allusions to the age of the case “would be clearly aimed at jury nullification,” the prosecutors argued.

Bonds’ five lawyers responded in a filing last week, “Defense counsel are well aware of the rules governing the admission of evidence and the proper limits on closing argument.”

But they said prosecutors shouldn’t be allowed to impose ground rules in advance that could interfere with Bonds’ constitutional right to defend himself and cross-examine witnesses.

For example, the defense attorneys said, prosecutors want to introduce evidence of Bonds’ athletic accomplishments to show that he had a motive to lie to protect his reputation, and yet want to make the same subject off-limits to the defense.

The four areas outlined by prosecutors “may well be relevant” to the defense, said the attorneys, who urged the judge to wait until prosecution evidence is presented at the trial before she evaluates whether the defense response should be limited.

Jury nullification has roots in English common law, but reached a turning point in a 1670 trial in London in which William Penn and a colleague were accused of creating an unlawful assembly by preaching Quaker principles on a city street.

Four members of the jury refused to convict them, despite being jailed for two nights without food by the trial judge, and were later each fined 40 marks for failing to convict.

When juror Edward Bushell appealed the fine, a higher court said jurors can’t be punished for their verdicts.

In America, jury nullification saved colonial publisher John Peter Zenger from being convicted of sedition against the British government in 1735, and in the 19th century Northern juries sometimes refused to convict abolitionists who helped runaway slaves.

But as psychology professor Irwin Horowitz wrote in a journal article, “Without question, the jury’s nullification power also has a dark side,” since some white Southern juries in the late 19th and 20th centuries refused to convict whites of violent crimes against blacks.

In recent years, supporters of federal legalization of medical marijuana and other drugs have advocated jury nullification.

When Oakland medical marijuana activist Edward Rosenthal was tried in federal court in San Francisco in 2003 on cultivation charges, prosecutors won a ruling from U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer barring any evidence or argument that could lead to jury nullification.

That order, later upheld by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, prevented the defense from suggesting that jurors disregard federal laws that criminalize marijuana and make no exception for California’s medical marijuana statute.

But during the trial, an outside group on the steps of the Federal Building–the same courthouse where Bonds will be tried–distributed cards supporting jury nullification.

Titled “Jurors Have the Power,” the small cards quoted Alexander Hamilton as saying in 1804, “Jurors should acquit, even against the judge’s instruction…if exercising their judgment with discretion and honesty they have a clear conviction that the charge of the court is wrong.”

There is no indication that the fliers were seen by Rosenthal’s jurors, who convicted him.

Several jurors later disavowed their verdict, however, after learning that Rosenthal was not allowed to argue a medical marijuana defense. After the conviction was overturned for unrelated reasons, a second jury found him guilty in 2007 and he was sentenced to one day already served in jail.

The current law on jury nullification in federal courts in the West was summarized by the 9th Circuit in a 2005 ruling upholding a murder trial judge’s decision to dismiss a jury candidate who said he believed in jury nullification.

“Importantly, while jurors have the power to nullify a verdict, they have no right to do so,” the appeals court said.

The court noted that jurors can’t be punished for a nullification verdict and that such a verdict can’t be appealed. But it said that nevertheless, “No juror has the right to engage in nullification … and trial courts have the duty to forestall or prevent such conduct.”

The appeals court has authority over federal trial courts in nine western states, including California.

Prosecutors in the Bonds case cited the panel’s words on the duty of trial judges in their Feb. 14 motion before Illston.

In their final response filing last week, the federal attorneys reiterated their claim that the four possible nullification arguments they outlined “are all impermissible.”

They said their motion does not interfere with Bonds’ constitutional right to present a defense.

“It only asks the court to ensure that the defendant’s defense stays within the limits of the law,” the prosecutors wrote.

Julia Cheever, Bay City News

Want more news, sent to your inbox every day? Then how about subscribing to our email newsletter? Here’s why we think you should. Come on, give it a try.